An appreciative chuckle spreads across my neighborhood Paris theater. In the preview onscreen, a graying psychiatrist has just asked his pink-cheeked sixty-odd-year-old patient whether the sexual assaults that destroyed his political career were worth it.

“Yes,” he replies unflinchingly. “They were worth it.” The music swells. The camera cuts to three nubile faces on a pillow around his: “What would you have wanted me to do instead, Doctor? Play golf?”

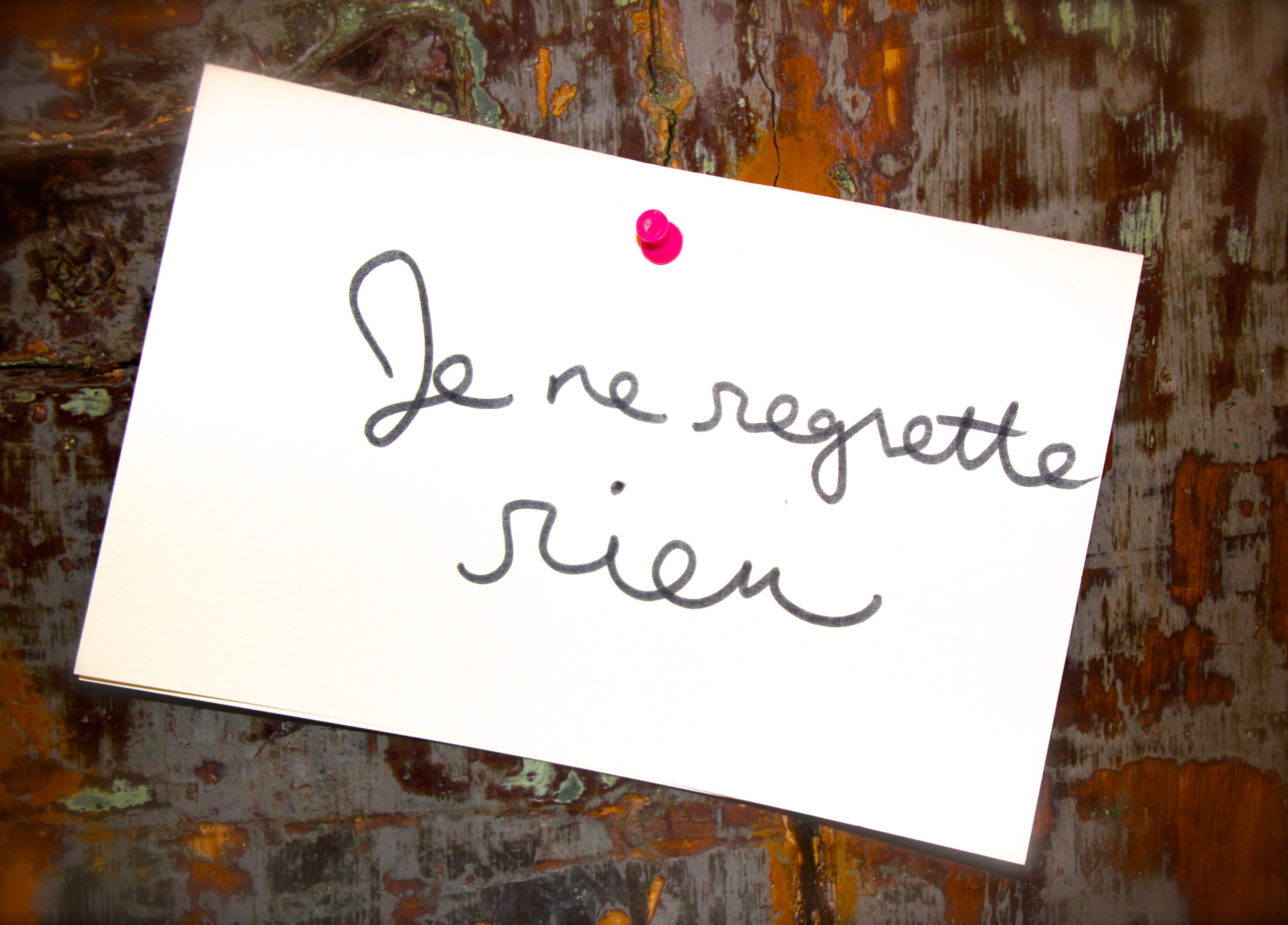

Welcome to New York feels like an Edith Piaf song, Je Ne Regrette Rien. “I regret nothing,” it seems to belt on behalf of its subject, past International Monetary Fund Director-and-French-presidential-hopeful-turned-alleged-rapist, Dominique Strauss Kahn. DSK (as he’s known on his home turf) threw it all away for violent sex: prostitution rings in Lille, attempted rapes of Paris reporters, a 2011 attack on a maid at Manhattan’s Sofitel. French audiences seem sympathetic.

American director, Abel Ferrara—who had his film acted, produced and distributed in France with local stars, and whose French producer boasts it earned back its costs in less than two weeks–has gauged his Gallic target audience well. DSK’s reputation is much on the mend in my adopted country, cinema aside. News stands are full of good tidings of his economic comeback after his billionaire wife divorced him in the wake of the Sofitel trials in New York. (He got off on the criminal trial less because anyone thought he was innocent than because his accuser was judged also to have imperfect credibility. In the civil suit that followed, he settled with her.) Magazines can’t get enough of his beaming, bow-tied face and “aggressive” criticisms of Socialist rival, Francois Hollande. One of the larger news weeklies, L’ Express, even ran a two page fictional account in May fantasizing how things might have been be if he’d won the 2012 French presidential election instead of Hollande. (Read: better than they are.)

Even DSK’s trademark initials are showing up again everywhere—not only on financial consulting firms but on swinger clubs in Belgium like Dodo Sex Klub (DSK) and party packages in Cannes. Dirty Sex Kits (DSKs) were proudly distributed on the evening of the awards ceremonies. They featured whips, handcuffs and condoms, and dispensed quickly with any notion that the film about DSK might have been intended as a critique of the man.

Far from being punitive or lamentatory, Welcome to New York is celebratory and bacchanalian—and that is one of the reasons that France’s biggest screen star embraced it. The huge-bellied Gerard Depardieu is far more of a driving force in Welcome to New York than its American B-director (who recently complained to French interviewers that his last movie was seen by “about 12 people”). Depardieu financed a big part of the film himself, and then played the key role for a fraction of what he usually demands: “I’m doing this film for nothing,” he repeatedly told the French press. He even lent his name to the hero: DSK is not called DSK in the film, he is called “Devereux.”

What drew Depardieu to this unsympathetic financier? My guess is it’s his virility—his willingness to provide a boorish, swaggering semi-criminal counterpoint to what Slate editor Hanna Rosin has dubbed “The End of Men.”

DSK and Gerard Depardieu are both men’s men: Every slab of their abundant flesh smacks of testosterone. It may be no accident that Depardieu is pals with Vladimir Putin, himself on film last week telling French journalists: “One shouldn’t engage in debate with women. They’re not strong—but, then again, strength is not what we appreciate in women.”

Such quotes would make most modern hearts fall, but they seem to make Depardieu’s nether regions rise–as does the catastrophic pre-coital small-talk he engages with some of his sexual partners in the film: “Honey, what do you do? You’re pretty. Do you know you’re pretty?” There’s some reason to suspect such lines are improvised by Depardieu—especially since they resemble the way he himself sounds in recent interviews: drugged, resourceless, incoherent, but groping for his manhood. Thus, Depardieu’s only concrete, on-the-record criticism of Devereux (other than that “I don’t like politicians”) is that he can’t grasp how any guy “can get off in less then six minutes.” He does not disapprove the morality of the figure his new film presents as a repeat wanna-be rapist, he just wants us to know that he himself has more sexual stamina.

The only thing resembling this sort of unlikely one-upmanship in the French press may be DSK’s criticism of President Hollande, jilted a couple of months back by second mistress, Julie Gayet, with whom he had cheated on first mistress, Valerie Trierweiler, via a number of much-publicized scooter-trysts. DSK mocked Hollande mercilessly. The rough-housing rapist confidently called the ham-fisted cheater black. Welcome to Paris.

So is there anything redeeming in all of this? When I saw the preview, I had hoped the film itself would be more nuanced and more intelligent; I had hoped I could use it as a vehicle to say something about French culture, which is one of the reasons I live and love here, and which stands in some contrast to the US. For all the much commented propriety of the French people with regards to how they bring up kids, organize meals and parcel out academic grades, there is a real acceptance for romantic improvisation, imagination, messiness and innate risk.

Where my American friends are prone to cry “foul” if an evening or an entanglement do not proceed as they have soberly envisioned–if a commitment is not offered in a timely manner or a sexual overture proceeds too quickly–my French compatriots have a suppler view. They do not appear to have the work ethic Americans sometimes bring to their intimate lives. They are more process-oriented, even adventure-oriented. If a relationship does not “go somewhere”–or if it goes too far too fast, sped along, God help us, by a glass of wine–they do not beat themselves up about it, they chalk it up to passionate excess and scoot along to the next thing, like their president–but usually more gracefully. (That would not be hard.) Je ne regrette rien is indeed a national anthem when it comes to the life of the senses and the soul.

But none of this is evidence in Welcome to New York—or rather, only the darkest flip side is in evidence. DSK’s ugliest orgies are depicted, his alleged aggressions voyeuristically documented. And while the film has been criticized here for bad lighting, bad sex scenes and the mean-spirited way “DSK” speaks of his wife’s family in an argument, it’s fairly obvious that audiences are at most minimally outraged by the film’s central sexual contentions about their almost-president. His hand today is stronger than it ever was since 2011.

When the film came out at the end of May, DSK threatened to sue for its assumption of his guilt in the Sofitel. In the meantime, he must have realized that his country people don’t really care.

A lover of hyperbole, I would be happy to say France loves a rapist while America criminalizes seduction—but find I can say neither. What I can say is that like many a willful and electric couple, Paris and New York have a vast amount to learn from each other–and they might do so quickly, lest one or the other proposition above become true.